In 2012, members of the Quinault Indian Nation in Taholah, Washington, finally decided to move their frequently-flooded seaside village to higher ground. Five years later, they had developed a master plan outlining a new town. Today, however, due to a lack of funding, only a single building has been constructed.

Quinault Indian Nation, Taholah, Washington

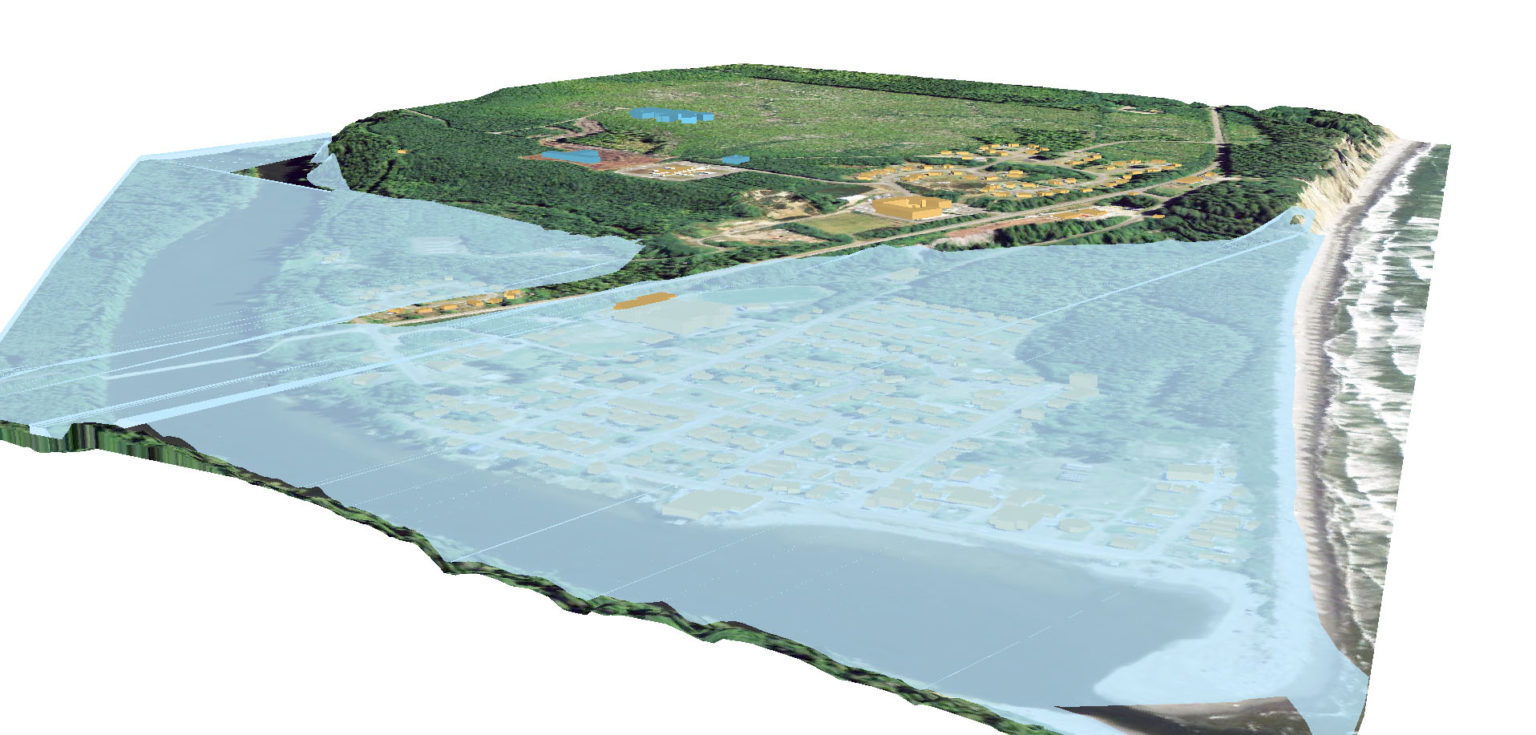

- An aerial view of the Quinault Indian Nation village of Taholah in Washington State. (Credit: Larry Workman)

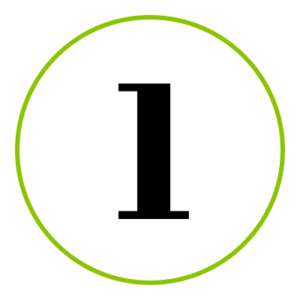

- Plans indicating the extent of flooding that a tsunami could bring to Taholah.

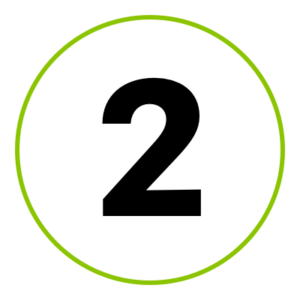

- Illustration of the location and size of the new inland village.

In Socastee, South Carolina, working-class residents whose homes are frequently inundated successfully banded together after their individual pleas for help to elected officials went nowhere. Now they’re waiting for FEMA to buy their homes—but whether they can afford to move anywhere in the area is an open question.

Around the country, a concept is increasingly being discussed as a response to the extreme weather and rising seas caused by climate change. Some call it managed retreat; others refer to it as climate migration or strategic relocation. Regardless of the phrase, it is the intentional movement of people, buildings, and infrastructure away from high-risk areas, a process that can be both complicated and sensitive. That includes relocation from coastal regions where the sea is encroaching, as well as from areas that have become increasingly less habitable due to heat, fires, mudslides, or riverine flooding.

Terminology matters

Managed retreat: This is the phrase used by many officials and researchers to describe the coordinated movement of people, buildings, and infrastructure away from climate-related risk, but it is not uniformly agreed upon.

Some Americans object to a concept they associate with defeat. Others point out that the phrase includes an inherent power dynamic: who is doing the managing, and who is being managed?

Instead, organizations working directly with impacted communities use terms like “climate migration” or “strategic relocation.”

Like Taholah and Socastee, many places throughout the U.S. are already experiencing some form of managed retreat, as residents take advantage of state and federal disaster dollars to move to new locations. But it’s currently happening on a very limited basis and in an ad hoc fashion—both of which, experts say, will have to drastically change if the nation is to effectively respond to the risks posed by climate change.

“We’re moving from this idea of buying up a handful of homes to, instead, ‘What would it take to relocate Miami?’” says A.R. Siders, a professor at the University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center. “That’s a massively different discussion in terms of scale and timeline.” Indeed, a 2018 report estimated that 300,000 coastal homes, valuing about $117.5 billion in total, are at risk of chronic inundation by 2045.

A GAO report released in 2020 outlined just how unequipped the federal government is to tackle the range of relocations that will be needed over the next decades—in part because no single federal agency has the authority to lead the process. Efforts to move small native communities in coastal Alaska and Louisiana, for example, have stretched out for over 20 years, largely because of the number of government players involved and the lack of clarity in their roles.

FEMA recently adjusted its flood insurance premiums to more accurately reflect risk, which could nudge homebuyers in the direction of less disaster-prone properties. And there are signs that the private market is responding in a similar way.

It is critical that architects understand the social, political, and economic ramifications of this type of climate adaptation. AIA’s Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct states under CANON VI, Obligations to the Environment, Climate Change, that “Members should incorporate adaptation strategies with their clients to anticipate extreme weather events and minimize adverse effects on the environment, economy, and public health.” And architects are increasingly being expected to conduct vulnerability assessments that take the best available climate science into account in order to determine a structure’s vulnerability in the face of potential risk.

But many architects are going beyond assessments to address the urgency of the issue. Some are designing buildings that directly respond to climate risks like flooding. Others are envisioning structures that, depending on a region’s potential for climate-based hazards, can be easily decommissioned and their materials reused if the site becomes no longer viable. And still others are playing a long game, designing flexible buildings that can respond to possible population changes a few decades into the future, depending on a community’s potential to gain or lose population due to climate hazards.

Listening to what residents want and need

Still, effectively addressing climate relocations will be a giant challenge. And doing it equitably is another matter. Historically, low-income communities have often been relegated to low-lying areas—and not by choice. For Black and indigenous communities, in particular, those regions may have been the only properties available to them. And many have been victims of underinvestment for decades.

These areas could face larger scale hurdles. In some places, for example, residents may need assistance navigating the often-labyrinthine process of applying for a buyout following a natural disaster—especially in cases where the land is heirs’ property and lacks a clear title. In others, redlining and exclusionary zoning have meant that the homes have long been valued less, and could make it far more difficult for residents to afford comparable housing elsewhere. They could also be underwater on their mortgages, disabled, or elderly.

According to a report by FEMA’s National Advisory Council issued in 2020, FEMA and the buyout process have consistently benefited white communities over predominantly nonwhite ones. Climate relocation has real potential to further exacerbate those inequities.

It doesn’t have to be that way, say advocates who are trying to create more effective methods for assisting low-income communities. But the development of new paths and policies to address these discrepancies is still very much a work in progress. “I don’t think there’s a blueprint for how to do this,” says Janice Barnes, AIA, co-chair of AIA’s Resilience and Adaptation Advisory Group. "But there are many, many people who are working on some part of this or other.”

Anthropocene Alliance is one of the organizations focused on how to do managed retreat equitably. The group has helped lower-income communities, including the one in Socastee, South Carolina, organize in order to get assistance from FEMA.

“It’s hard to navigate or even get attention—once the water’s gone, everyone forgets about it,” says Terri Straka, a homeowner in Socastee’s Rosewood neighborhood, which has been repeatedly flooded by the nearby Intercoastal Waterway. She says coming together as a group was key to getting assistance but doesn’t know if she’ll be able to remain in the region once FEMA puts a value on her house. “I’ve been in this area since I was 16; it’s kind of in my DNA. But it’s a difficult time to find anything that’s comparable.”

Recently, Anthropocene Alliance released a 10-point statement that was the outcome of discussions between grassroots leaders from 10 low-income communities from places like Port Arthur, Texas, and Biloxi, Mississippi. The first item expressed in the statement? “Before anything else, let’s talk, reason, and learn together.”

The ten-point platform on climate migration

In 2021, Anthropocene Alliance and the Climigration Network convened a series of roundtable discussions among leaders from ten low-income, Black, Latinx, and Native American communities. They created a 10-point platform on climate migration. The full version can be found here.

Before anything else, let’s talk together.

Before anything else, let’s talk together.

Stop development in places vulnerable to excessive heat, drought, floods, or fires.

Stop development in places vulnerable to excessive heat, drought, floods, or fires.

Have patience while we carefully consider migration.

Once we’ve made the decision to migrate, don’t make us wait forever.

Once we’ve made the decision to migrate, don’t make us wait forever.

Will government payouts be enough to let us buy safe houses in nice neighborhoods?

Will government payouts be enough to let us buy safe houses in nice neighborhoods?

Nobody should profit from our distress.

Nobody should profit from our distress.

Systemic racism makes all other inequities worse.

Systemic racism makes all other inequities worse.

Federal and state governments need to acknowledge racism and oppose it.

Federal and state governments need to acknowledge racism and oppose it.

Pay attention to receiving communities as well as migrating ones.

Pay attention to receiving communities as well as migrating ones.

Climate migration is a fundamental issue of justice and demands a commensurate federal response.

Climate migration is a fundamental issue of justice and demands a commensurate federal response.

The alliance and other advocates emphasize that whatever process is occurring—whether government officials are discussing the construction of protective infrastructure, or explaining the intricacies of a buyout program—it shouldn’t be a wholly top-down experience.

But community-led processes currently aren’t being used as widely as they could be, says Kristin Marcell, director of the Climigration Network, which brings together practitioners and community leaders. Instead of collaborating with community-based organizations, policymakers and planners often create their plans beforehand, then simply present them for approval. “I see a reticence to actually develop a relationship with community members,” Marcell explains.

For architects who are being brought into a process that’s already begun, she adds, it can be especially difficult. “If there hasn’t been a building of trust before they come in, they could be asked to design a solution that wasn’t what the community needed, and it becomes very difficult to engage the community.”

Marcell recommends architects be proactive by asking questions before joining a project: How has the community been engaged so far? Were residents involved in the program’s design and selection? What are they saying they want?

Her organization recently developed a guidebook outlining how to have more collaborative discussions. Many of the techniques listed there are similar to those developed by AIA’s Guides for Equitable Practice and its Communities by Design program.

Advocates emphasize that every community is unique in its needs and desires. For example, land and place can be culturally significant to Black, indigenous, and other historically excluded groups, and some may want to stay where they are due to that sense of connectedness. But other communities that have historically been in harm’s way may be eager to leave for higher ground. Some may wish to be relocated en masse, an approach that isn’t well supported by existing policies; others might not care.

Learning when to say no to projects

Ensuring that lower-income homeowners not only get fair value for their houses but can actually afford to buy somewhere else remains a very serious challenge. The nation is already experiencing an affordable housing crisis, and experts expect it to get worse in many places, as higher ground becomes sought-after and expensive. But it’s especially critical that Black and indigenous homeowners—for whom homeownership may be the key vehicle for intergenerational transfer of wealth—are able to purchase new homes.

In response, analysts and academics around the country are developing creative ideas to offset that pricing disparity. For example, Buy-In, a nonprofit organization working with flood-prone communities and individuals, is examining the possibility of partnering with conservation groups to convert formerly residential properties to open space assets. Returning the land to green space that acts as a carbon sink could make projects eligible for climate mitigation funding—and those dollars could be used as additional financial support for the area’s former residents.

Another big unknown is where those residents will go. Some might move to another part of town, but without communication between local, state, and federal officials, they may well wind up in another flood-prone zone.

“Those conversations tend to happen in different offices; they’re not coordinated,” says Siders. “We need them all to be sitting down together talking about, ‘Where does it make sense to increase density?’”

With robust community participation, sufficient funding, and swift, coordinated government action, it’s possible that the relocations could wind up being a win-win for everyone. Climate migrants could potentially move to downtowns, which are frequently on higher ground, densifying them in the process. They might even go to regions of the country like the Rust Belt, where urban infrastructure is currently underutilized.

“There are plenty of places in the U.S. where we have the opportunity to reinvigorate our town centers through in-migration,” says Jesse Keenan, a professor of real estate at Tulane University’s School of Architecture. He views the relocation process as a chance to enhance the built environment. “This can be a once-in-a-generation opportunity to make investments in sustainability—transit-oriented development, high-performance buildings. We can’t just recreate suburban sprawl.” Much of this thinking about how to sustainably densify and upzone central cities is already occurring among architects and planners in research centers and think tanks around the country.

But the experience of the Quinault Indian Nation illustrates just how far the U.S. is from seriously implementing those ideas. While tribal groups have unique characteristics, given that they’re self-governed, their experiences can be instrumental for other coastal communities. Located on Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula, the village of Taholah has been vulnerable to flooding and tsunamis since the early 2000s. In 2012, residents voted to move a half-mile inland and conducted community-wide meetings to solicit feedback and create a master plan—one that outlines a more sustainably-designed town with a wider array of housing options.

But resettling an entire community of 665 residents is still a very heavy lift, especially for a Native American tribe whose government affiliations and funding sources are particularly convoluted. So far, only one building has been constructed: a community space that houses a senior center and a daycare.

It’s clearly going to be a while before the U.S. is ready to undertake climate-based relocations on a big scale. Until then, though, planners and analysts say there is one very big step architects can take to respond to climate change-driven emergencies: Stop building in flood zones.

Or at least, says Barnes, the co-chair of AIA’s Resilience and Adaptation Advisory Group, “Learn when to say no to projects.” She adds, “At the end of the day, we have to change the way we experience certain environments.”

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the sources interviewed and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The American Institute of Architects, nor the endorsement of any companies listed.