To reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, architects are looking beyond their own projects to make a greater difference in a new way—with building codes.

By 2060, the world is projected to add 2.5 trillion square feet of new building space, doubling the current global stock. Most of this growth will occur in cities, which are responsible for over 66% of worldwide energy consumption and more than 70% of energy-related CO2 emissions, leading to climate change and rising temperatures.

To help slow this trend, architects are creating coalitions and lobbying elected officials to adopt a “zero code”—a nationally vetted framework for designing buildings that create zero net emissions. “It’s important for every member of our population—including the most vulnerable—to have access to green construction and a healthier environment,” says Anica Landreneau, Assoc. AIA, director of sustainable design at architecture firm HOK in Washington, D.C. “Adopting a zero code is important because then green construction becomes universal.”

Designed to safeguard the health, safety, and welfare of communities, building codes are essential to addressing the most important issue of our era—climate change. We must reduce emissions from buildings in the next 10 years, which is the remaining window of time to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (34.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. To accomplish this, architects are working with communities to advocate for codes that make existing buildings more energy efficient, reduce the embodied carbon of building materials, and ensure new construction produces zero net emissions. “Building codes for cities are like the muscular system for the human body,” says Julie Hiromoto, AIA, a principal and director of integration at HKS Architects in Dallas. “As a society, we need our codes to be fit and healthy. And when we set ambitious goals, we’ll get there faster together.”

This is a challenge.

Across the United States, building codes are overseen by various levels of government, from city to county to state. As a result, establishing guidelines for zero-carbon buildings is difficult. Communities can disagree on their importance, and even if they want to implement zero codes, few municipalities have the resources to create them.

That’s why, in 2018, Architecture 2030 created the ZERO Code, a standard for building design and construction that combines efficiency standards with renewable energy to create zero net carbon buildings. In 2019, Architecture 2030 worked with the American Institute of Architects (AIA) to get the ZERO Code adopted as a voluntary appendix in the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), resulting in a set of nationally vetted guidelines, the Zero Code Renewable Energy Appendix. Because it’s an appendix, jurisdictions that adopt the 2021 IECC can choose for themselves whether to include the Zero Code as the minimum performance level for new buildings, or to combine it with a previous version of the IECC and require new buildings to be zero net carbon.

“Legislation that requires buildings to reduce and eventually eliminate their carbon footprint drives creative design thinking and market solutions,” Hiromoto says. “And the ZERO Code developed by Architecture 2030 is a starting point for local jurisdictions to adopt policies that support zero carbon new construction, working toward the ultimate goal of decarbonization that we so urgently need.”

In June, the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis issued a report recommending that Congress incentivize state and local governments to adopt the ZERO code. While supported by Democrats on Capitol Hill, this recommendation is unlikely to be adopted by the current administration.

In the meantime, architects are creating coalitions of their peers, mobilizing people outside the building community, and urging their elected officials to begin adopting the ZERO Code when their local building regulations are updated, helping to create real change.

“City, county, and state jurisdictions are all saying: I want to meet my carbon commitment, but how do I do that?” Landreneau says. “The ZERO Code is a voluntary appendix they can insert into their own regional code and modify as needed to reduce building emissions. This issue has little support at the federal level, so local leadership is crucial if we’re going to meet climate goals. This is a powerful tool to help you do that.”

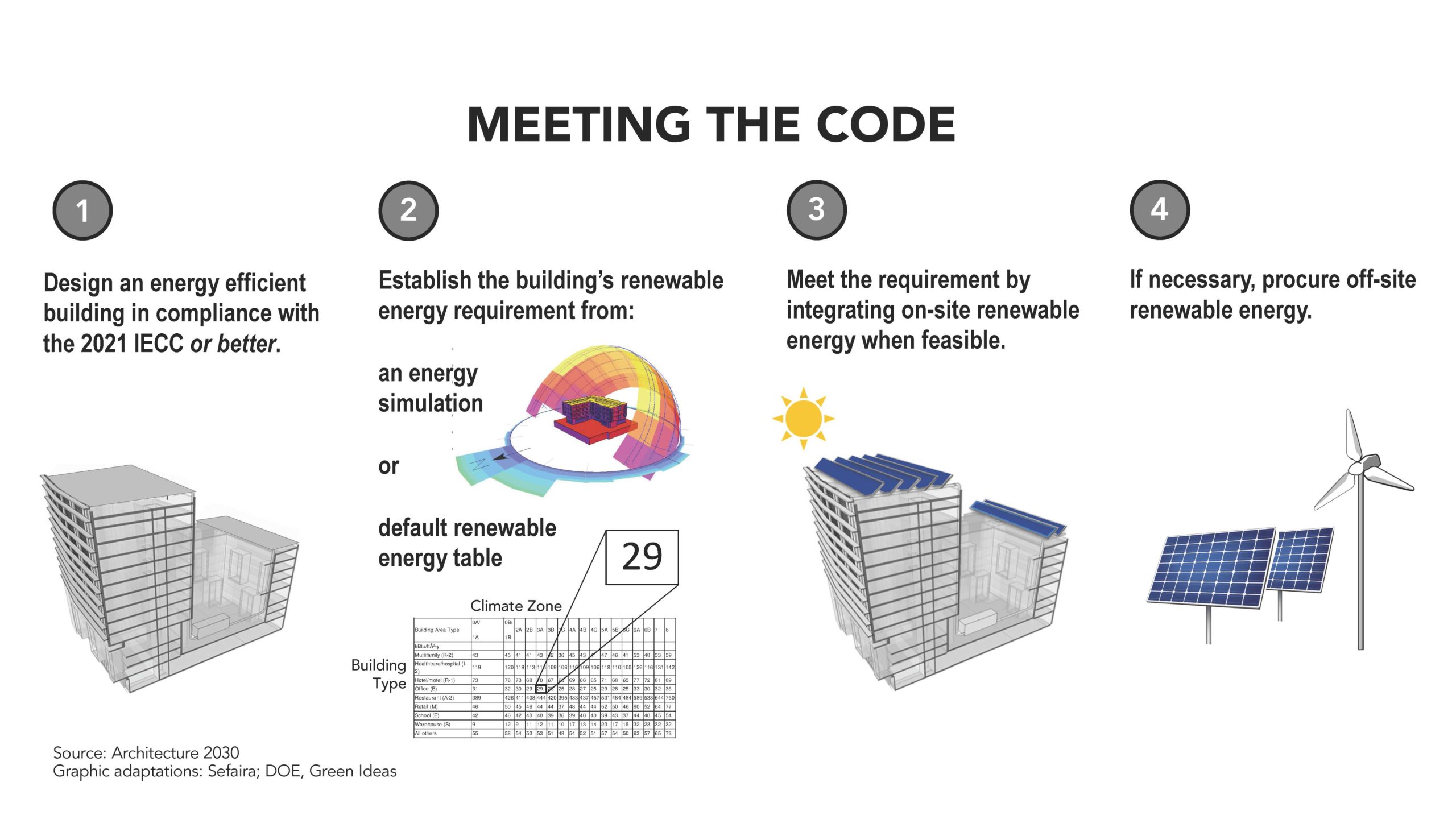

ZERO Code: A standard for new building construction that integrates cost-effective energy-efficiency standards with on-site and/or off-site renewable energy, resulting in zero net carbon buildings. It includes prescriptive and performance paths for building energy-efficiency compliance based on current standards that are widely used by municipalities and building professionals worldwide. Here’s how it guides jurisdictions to reduce emissions.

1) Design an energy-efficient building (efficient building envelope, daylighting, passive heating, cooling, ventilation, efficient systems, equipment, controls).

2) Address the building’s remaining energy needs with on-site renewable energy and/or off-site renewable energy (wind, solar, hydro, and other non-CO2-emitting sources).

Create Coalitions with the Building Industry

To get the ZERO Code adopted by local, county, or state governments, building coalitions to advocate for them is essential. Architects can find common ground and create a foundation for influencing municipal or state boards by starting a conversation around the ZERO Code with engineers, home builders, building officials, and commercial developers. “Coalition building is essential,” says John Nunnari, the executive director of AIA Massachusetts. “It’s a much more effective strategy than trying to propose the ZERO Code on your own, and usually the different groups within the building industry can agree on its importance.”

![]() “It’s important for Michigan to adopt the ZERO Code Renewable Energy Appendix when it updates the state energy code. Appendices are considered optional guidelines. That way, local jurisdictions can adopt it if they choose to, and usually appendices become standard code.”

“It’s important for Michigan to adopt the ZERO Code Renewable Energy Appendix when it updates the state energy code. Appendices are considered optional guidelines. That way, local jurisdictions can adopt it if they choose to, and usually appendices become standard code.”

—Jan Culbertson, FAIA, senior principal at A3C architecture firm in Ann Arbor, Michigan

![]() “Architects and AIA chapters telling their building commissions they want to adopt the ZERO Code is having a huge impact. Adopting it also helps improve the ISO rating for the local community, which reduces the insurance costs for residents. So, there's a direct financial impact as well.”

“Architects and AIA chapters telling their building commissions they want to adopt the ZERO Code is having a huge impact. Adopting it also helps improve the ISO rating for the local community, which reduces the insurance costs for residents. So, there's a direct financial impact as well.”

—Kristopher Stenger, AIA, assistant director of building permitting and sustainability in Winter Park, Florida

![]() “If cities are required to enhance their buildings’ performance, the demand for training, tools, and resources that reduce carbon dioxide will also increase. This prioritization will drive positive change and empower all developers, building owners, and operators to take responsibility and do what’s necessary to curb global warming now, instead of depending on a bailout that isn’t coming. We have one planet, and humanity’s survival depends on it.”

“If cities are required to enhance their buildings’ performance, the demand for training, tools, and resources that reduce carbon dioxide will also increase. This prioritization will drive positive change and empower all developers, building owners, and operators to take responsibility and do what’s necessary to curb global warming now, instead of depending on a bailout that isn’t coming. We have one planet, and humanity’s survival depends on it.”

—Julie Hiromoto, AIA, principal and director of integration at HKS Architects in Dallas, Texas

Build Broader Alliances

Next, architects must build alliances with people outside their profession. Every community has citizens and environmental organizations that believe in sustainability, but that may not know how building codes can make an impact. By engaging with these groups and explaining the merits of zero codes, architects can enlist others to support the cause and expand the movement beyond the building industry.

“There’s a low barrier to entry to getting involved in code development,” says Kristopher Stenger, AIA, the assistant director of building permitting and sustainability for the city of Winter Park, Florida. “When architects, building owners, and citizens all push for these things, it really brings it to the forefront for elected officials. You can also reach out to sustainability directors in surrounding communities to make a broader coalition of towns to push things forward.”

![]()

“The one thing that architects and engineers agree on is that the worst way to draft a building code is through legislation—and the best way to do it is through regulation. Regulators know that legislators are watching them, and if they’re not doing the things requested of them regarding energy efficiency, the legislature can force their hand. This is a useful political tool to move the needle for sustainability.”

—John Nunnari, executive director of AIA Massachusetts

![]() “When the 2021 IECC code gets published this year, I think you’re going to see a lot of cities adopt it. Around 80% of our population is in cities, so I think it’s okay if the ZERO Code gets adopted there before the state level. And a great tool for cities that are thinking about the ZERO Code is the ‘stretch code’ model, in which you phase it in and incentivize early adoption. In Montgomery County, Maryland, for instance, builders get 75% off their property taxes for five years if they design a Platinum LEED building—a pretty compelling deal.”

“When the 2021 IECC code gets published this year, I think you’re going to see a lot of cities adopt it. Around 80% of our population is in cities, so I think it’s okay if the ZERO Code gets adopted there before the state level. And a great tool for cities that are thinking about the ZERO Code is the ‘stretch code’ model, in which you phase it in and incentivize early adoption. In Montgomery County, Maryland, for instance, builders get 75% off their property taxes for five years if they design a Platinum LEED building—a pretty compelling deal.”

—Anica Landreneau, AIA, the director of sustainable design at HOK architecture firm in Washington, D.C.

Advocate for Adoption

Finally, architects must coordinate their coalitions to communicate their desire for zero codes to the regulators or elected officials who adopt and enforce building codes, as well as those officials’ supervisors—ensuring the message is heard at all levels of government. If your state oversees the building code, then reach out to your governor and state code authority. If it’s managed by your city, then request a meeting with your mayor and city council and show up as a large group. “If you can hit all fronts at the same time, you can really move the ZERO Code forward in your city, county, or state,” Nunnari says. “Instead of simply reaching the board that’s writing the building code, you’re also going to the officials above them and saying, ‘This is important, we need to do this, and here's why.’ And that can drive real change.”

Four resources to help you advocate for Zero Codes in your area

- Your local AIA: There’s strength in numbers, and it’s important to connect with allies in your area. Your local AIA chapter can help you find groups and organize one of your own.

- Talking points: AIA can provide you with custom talking points to use for letters, emails, presentations, and other collateral.

- SpeakUp legislative guide: Study the five key elements of conducting a successful legislative campaign in our guide. You’ll learn about legislative strategy, message development, fundraising, and organizational growth.

- Technical resources and support: Two key resources are the Zero Code Renewable Energy Appendix itself and a webinar that addresses the appendix and how compliance can be achieved.

The Blueprint for Better campaign is a call to action. AIA is asking architects, design professionals, civic leaders, and the public in every community to join our efforts. Help us transform the day-to-day practice of architecture to achieve a zero-carbon, resilient, healthy, just, and equitable built environment.