The first thing you notice in your dream of living with renewable energy is the noise—or lack of it.

In the future, when solar panels and other innovations have enabled the United States to power the country with renewable energy, you will awaken to a new reality: A very quiet one. Without combustion engines, citizens will open their windows to the faint whoosh of trees swaying in the breeze, of battery-powered public transport and sidewalk scooters passing by, and of hyperefficient mini-split units cooling or heating their homes. All this will be powered by rooftop renewables on a local microgrid that sells people’s unused energy to the grid—putting money in their pocket every day.

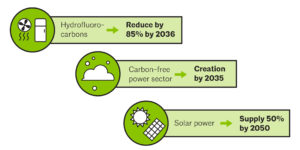

That vision may seem like wishful thinking, but it could happen sooner than you think. In September, the Biden administration announced an ambitious plan to reduce hydrofluorocarbons (HFC) in air conditioners and refrigerators by 85% over the next 15 years, create a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035, and transition to a net-zero economy by 2050. The administration estimates that by 2050, almost half of the nation’s energy needs could be met with solar power alone. Alongside innovations in residential solar panels—which were installed at record levels in 2020 and typically pay for themselves within six years—a renewable future truly seems on the horizon.

And it’s just in time. According to a recent report by the United Nations, humanity must innovate cleaner energy sources or the earth could warm by as much as seven degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century, with catastrophic results. One of the largest contributors of global emissions? Buildings. In total, the built environment accounts for about 40% of annual fossil-fuel carbon-dioxide emissions (CO2), leading to increases in flooding, fires, and hurricanes, and causing billions of dollars in damage.

"Yet over time we’ve realized that fear doesn’t motivate change. To truly create a better future, we need to inspire—and share the positive aspects of a greener future."

The challenges of climate change are real. Yet instead of focusing on the negatives, scientists are increasingly highlighting a more hopeful vision—of a world improved by the switch to clean energy. “For more than 30 years, my colleagues and I have been trying to make people aware of climate change,” says Anne Waple, a climate scientist who heads Earth’s Next Chapter, an organization that helps educate businesses and create climate programs for nonprofits. “Yet over time we’ve realized that fear doesn’t motivate change. To truly create a better future, we need to inspire—and share the positive aspects of a greener future.”

To help spark change, architects are embracing an optimistic approach to rethinking the built environment. By 2060, the global building floor area is expected to double from its existing size of 2.4 trillion square feet—the equivalent of adding another New York City to the planet every 34 days. To help ensure that this growth is achieved with a zero-carbon footprint, The American Institute of Architects (AIA), the largest design organization in the world, is asking the industry to rethink how it designs, plans, and constructs for the future. “If everyone adopts clean-energy technologies, then the prices of these innovations will drop—look at solar—along with emissions,” says Vincent Martinez, Hon. AIA, the president and CEO of Architecture 2030, an organization dedicated to decarbonizing the built environment. “Architects are invaluable when it comes to creating this type of change at scale.”

Here’s an overview of what your daily life with renewable energy may resemble—and how architects can help make it a reality.

A new world for your senses

Noticeable the moment you wake up each morning, the replacement of combustible engines with battery power will create less noise both on the street and in your home, while also improving the quality of the air you breathe. Additionally, one of the primary culprits contributing to low air quality in domestic spaces is among the least obvious: Our gas stoves and heating systems. According to a 2020 report by the Rocky Mountain Institute, gas stoves—particularly when not up to code and unvented—can exacerbate health conditions like asthma by emitting levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) that exceed EPA guidelines. Overall, fuels in buildings contribute 10% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

The alternative? Renewable electricity powering much more efficient homes. In addition to electric ranges and ovens, mini splits are 300% efficient, which means that they’re three times better at heating homes than even the most efficient gas units. Recently, the Department of Energy launched the National Initiative for Clean Heating and Cooling Systems in Buildings to focus on scaling heat pumps and mini splits that utilize low to no GHG refrigerants. And with architects increasingly replacing steel and concrete with low-carbon materials (such as bio-based materials or carbon-sequestering concrete), and implementing passive strategies for heating and cooling, your everyday experience indoors and out will improve markedly. “When buildings incorporate things like living walls and shading to block solar gain, and apply green or cool roofs, we won’t feel as hot in the summer,” Martinez says. “By incorporating site-based strategies like vegetative cooling, we’ll experience a canopy effect walking through streets and buildings. Everything will feel cooler, similar to passing through a forest.”

The Future is Now

Here’s how green technologies are already improving our world.

- Real life application: Albion District Library, Albion, Michigan. The library features green spaces, Smart Surfaces, and bio-based materials. Winner, AIA COTE Top Ten Award 2018.

- Real life application: Discovery Elementary School, Arlington, Virginia. The largest zero-energy school in the U.S., Discovery has solar panels, Smart Surfaces, and a wooden roof. Winner, AIA COTE Top Ten Award 2017.

- Real life application: Tassafaronga Village, Oakland, California. The community includes green spaces, solar panels, and permeable gutters to provide a resilient and healthy living spaces. Winner, AIA COTE Top Ten Award 2015.

Cleaner air equals greater community equity

In addition to creating a richer everyday experience for the senses, a renewably powered world will bring about a more equal society. Currently, for instance, most city neighborhoods have dark-colored, impervious surfaces atop buildings and on streets. Yet dark roofs heat the surrounding air by 52%, raising cooling costs and energy consumption, while pavement facilitates runoff and flooding. All of these factors disproportionately impact residents in inner-city neighborhoods with the fewest number of trees—historically, low-income communities. “The way cities are designed today, low-income areas commonly get 10 to 14 degrees hotter than other, more affluent areas,” says Greg Kats, the founder and CEO of Smart Surfaces Coalition, a nonprofit working to transform urban spaces. “There are fewer trees, radiant heat is pouring off dark surfaces, and the air quality is bad. This means that kids aren’t outside and folks aren’t meeting on the streets or exercising, which results in higher crime and obesity levels.”

To improve environmental and social resilience in neighborhoods, architects are working with city planners to replace asphalt with smart surfaces to lower heat and increase public health and safety. In Oakland, California, for example, AIA architects helped create diverse affordable housing with Tassafaronga Village, a 7.5-acre community on a brownfield infill site remade with apartments, landscaped paths, a park, and more. Smart surfaces include reflective and porous pavements, green or reflective roofs, solar panels, and trees. These surfaces emit less heat, save money on energy, reduce emissions, and enhance quality of life. Indeed, according to “Cooling Cities, Slowing Climate Change, and Enhancing Equity,” a recent Smart Surfaces Coalition report for the City of Baltimore conducted with Vivian Loftness, FAIA, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, smart surface strategies can reduce peak downtown summer temperature by more than four degrees Fahrenheit while ultimately saving the city $13.5 billion in expenses over 30 years—resulting in $21,000 per resident that can be used for programs for community enhancement.

“Plans like this result in more trees, making communities feel much cooler and more shaded, with less air pollution,” Kats says. “People are outdoors, the community is more vibrant, and crime goes down. Overall, greater health means fewer sick days—kids spend more time in schools, have improved education, and get better jobs, ultimately putting that money back into the community to help everyone thrive. Architects are instrumental in accomplishing this because they can tell the story to institutions to help shift society to the greatest net benefits.” Kats adds that “Smart surfaces are one of the most cost-effective and most overlooked climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. It may also be the most effective way to promote urban environmental justice.”

A renewable-only future will enhance quality of life in rural areas as well. The current emission-intensive infrastructure for both energy and food production in the U.S. relies on centralized distribution—from power sources like coal plants and from large-scale agriculture hubs, respectively. But by transitioning to renewable microgrids, communities can use localized solar power when needed and distribute any surplus to the broader grid at a profit. Soon we may even be able to drive our electric vehicles to the grocery store, park them in charging stations, and have them refueled by rooftop solar panels atop while we shop, with excess energy powering the store in turn. And during extreme weather events, which have resulted in increasing numbers of blackouts across the U.S., most notably in Texas last winter, local renewable power—when paired with storage options like electric vehicles and battery-based home backup systems—will create resilient communities consisting of networks of homes able to power one another in the event that power lines to distant sources are severed. “In addition to localized energy, localized food production will reduce emissions while ensuring communities eat healthier,” Waple says. “All this leads to a brighter future.”

Powering a new future

Incremental change in our daily lives can transform the future and empower a new generation of workers in renewable energy. For centuries, racial and ethnic minority groups were disenfranchised from the built environment through practices like redlining. But to create the infrastructure necessary for a renewable world, new jobs will be needed to manage and grow these energy solutions.

Integrating renewable energy solutions in the built environment supports a strong renewable-energy market. When paired with job-training programs (both professional and in trades), supported at the project level by architects and contractors, minority communities can leverage that opportunity for economic advancement. GRID Alternatives, for example, offers strategies and tools for careers in solar energy, while MASS design pioneered an inclusive design approach in Rwanda by hiring local workers—a model that could be replicated more in the United States.

“Designing resilient buildings is important, but we also need to ensure that communities of color—which have traditionally been sidelined—help drive it. Architects can help.”

The construction trades are currently strapped for skilled people and are a huge opportunity for underserved communities. According to Denise Fairchild, the president of Emerald Cities Collaborative, a nonprofit dedicated to greening cities and enhancing equity, our society is on the cusp of national change—a moment that can reinvigorate communities. “Designing resilient buildings is important, but we also need to ensure that communities of color—which have traditionally been sidelined—help drive it,” she says. “Architects can help.”

In Fairchild’s vision, architects can guide the establishment of work programs at the intersection of local governments, professions, and trades in the built environment, helping to ensure a greener future for all. “Architects can be bridge builders to help create new jobs in infrastructure,” she says. “Renewable energy is a chance to innovate for economic opportunities, as well as the health of society at large—and I’m hopeful to see the movement already underway.”