Buildings often create two problems.

They contribute nearly 40 percent of the world’s fossil fuel carbon dioxide emissions (CO2), speeding global warming. And, historically, they have contributed to systemic racism and exclusion through practices like redlining that prevent certain people—often poor and Black—from accessing certain neighborhoods, typically wealthy and white. Both can be resolved with a simple practice, one that may be more widely adopted in the wake of COVID-19 and the recent uprisings over racial justice: renovation.

“Throughout history, the architecture of cities has changed after pandemics,” says Jean Carroon, FAIA, a partner with the Goody Clancy architecture firm in Boston. “Now it’s more important than ever to rebuild the world in a healthy, equitable way. With supply chains in flux, renovation allows you to buy locally while improving sustainability and creating equity through community investment. It’s the most logical thing we can do to lessen our impact on the planet.”

The world is on schedule to double its building stock by 2060. The buildings we create must meet zero-carbon standards. But just as important, we need to improve the performance of existing structures. Renovating buildings dramatically reduces embodied carbon, which is the carbon emitted during new construction by the manufacture, transport, and assembly of materials. As a result, architects can renovate existing buildings to reduce their operational carbon to zero, lessening their contribution to climate change.

“If you renovate and reuse the biggest parts of existing buildings—typically the structure and foundation—you can save 50 percent of your carbon on a project right off the bat,” says Larry Strain, FAIA, a principal at Siegel & Strain Architects in Emeryville, California. “It’s the first thing all architects and owners should try to do.”

Overall, renovating buildings to become net-zero carbon can have a tremendously positive impact, with three key benefits: creating more equity by strengthening local economies, making buildings more valuable, and ensuring we meet carbon goals—even in the wake of COVID-19.

A Map of the U.S. Building Stock

How existing structures in the United States offer opportunity for renovation.

![]()

Office buildings

Existing footprint: 18% of all existing commercial buildings

Opportunity: Office buildings built between 1946 and 1979 operate with a higher energy use intensity (EUI)—a prime opportunity for reducing CO2 emissions

![]()

Education buildings

Existing footprint: 14% of all existing commercial buildings

Opportunity: Buildings constructed before 2005 (about 75% of all education buildings) need improvement in efficiencies

![]()

Health care buildings

Existing footprint: 5% of all existing commercial buildings

Opportunity: Surprisingly, the EUI of new buildings is rising compared with renovated buildings, possibly from demands for newer technology, requiring design ingenuity to lower consumption.

![]()

Hotel buildings

Existing footprint: 5% of all existing commercial buildings

Opportunity: More than 20% of existing hotels have been built since 2000, and EUI levels in those structures are rising, presenting a chance for architects to both rethink future designs and renovate newer existing stock.

![]()

Retail buildings

Existing footprint: 15% of nonresidential construction spending in the last decade

Opportunity: The retail sector is difficult to assess because of its diversity, but has seen a third of its stores built since 2000. This is a higher proportion of new construction compared with other sectors, and the buildings consume more energy than previous generations—an opportunity for architects to reduce the EUI of both new construction and newer existing stock.

Creating Inclusion and Equity

Retrofitting buildings can create more inclusion and equity through community engagement and reinvestment. Compared with new construction, a larger proportion of a retrofit’s budget often goes to local labor, creating more jobs with each dollar spent. In 2017, for instance, renovation and retrofits accounted for 43 percent of architecture firm billings in the United States, with much of that likely going to local contractors and communities.

The EastPoint Project in Oklahoma City, for instance, is even helping to revitalize an entire community. Established in 1889, the once thriving East Side neighborhood lost most of its business over the previous few decades, experiencing no new development for the past 35 years and having just one small grocery store to serve the entire community.

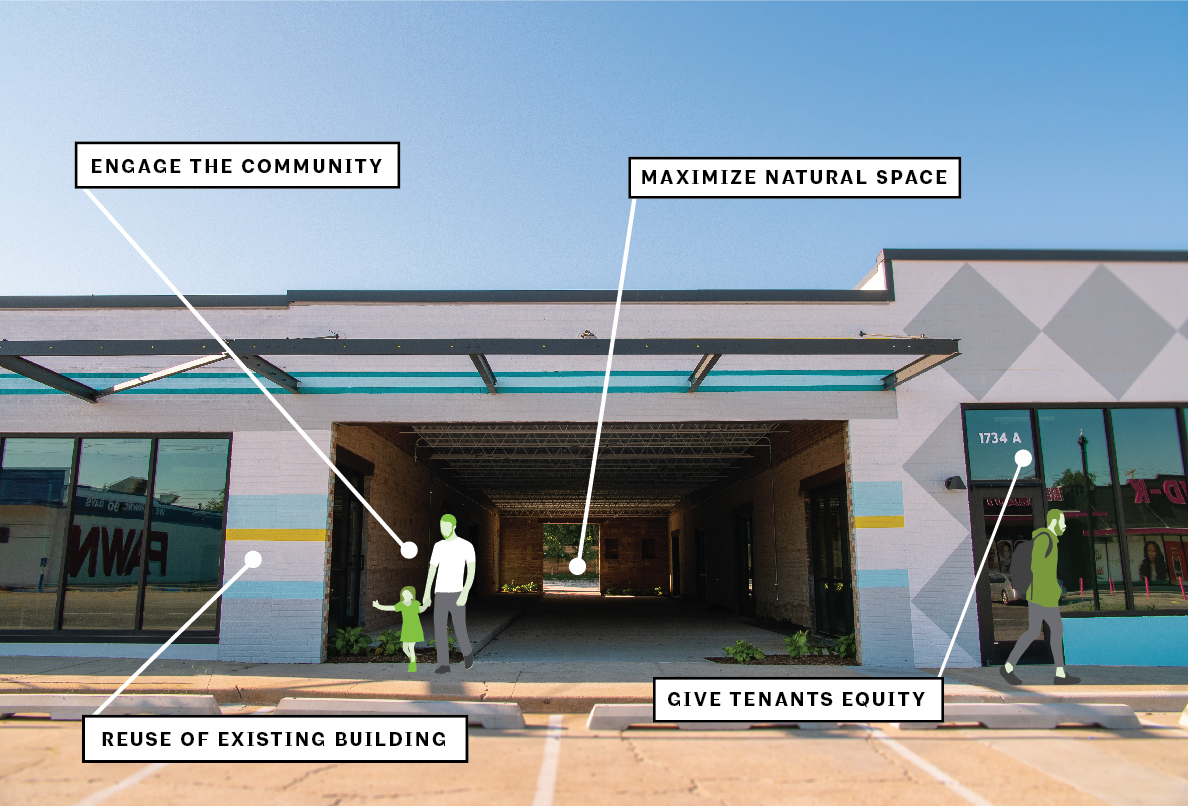

To turn things around, Sandino Thompson—a trained engineer who works as a developer—partnered with Nikki Nice, now a local councilwoman, developer Jonathan Dodson, and architects Jeremy Gardner, AIA, and Hana Waugh, AIA, of the Gardner Studio, to showcase how renovation can revitalize communities. They turned a former strip mall into a community hub. “People were saying Oklahoma City was having a renaissance, but that wasn’t quite true,” Thompson says. “The community I grew up in is traditionally African American, and has suffered from decades of redlining and discriminatory racial policies. So I wanted to come back and help bring it to life—to build for unity.”

Waugh, who has since left the Gardner Studio, agrees. “We wanted to reimagine the American strip mall,” she says. “We often reuse existing buildings, and here that was particularly important, because of concerns about gentrification. Renovating makes sense financially, helps reduce the carbon footprint, and can be a symbol for reinvesting in the community. We aren’t here to push anyone out.”

The 40,000-square foot EastPoint Project now hosts a variety of local businesses and has become an economic engine for the community, even creating equity for tenants. When designing the project, Gardner and Waugh opened up the site to the community, adding sidewalks, a central breezeway, and floor-to-ceiling windows, making tenants visible and accessible. Then Dodson ensured each of the tenants received a 15 percent stake in their lease, creating ownership to encourage growth and build wealth. “We hear a lot about gentrification and displacement,” Thompson says. “So we created a space where minority tenants can have 15 percent ownership and be part of the landlord group. It’s a more inclusive way of developing, ensuring everyone participates in the economic gain.”

How Renovation and Reuse Can Create Equity and Inclusion

Three ways updating buildings improves communities

- Renovating a single building can spur investment in the community, but it needs to be done with purpose to avoid gentrification.

- Be intentional about local participation and engagement to meet the needs of the community as well as the owner.

- Investment in local entrepreneurs and businesses can help build multigenerational wealth across an entire community.

Enhancing the Value of Buildings

Renovating and reusing existing structures makes buildings more valuable. According to a 2018 poll by Dodge Data and Analytics, 94 percent of building owners in the United States believe their properties are worth more after a green retrofit. In addition to saving money by using resources more efficiently, renovation attracts buyers and tenants seeking spaces that help reduce climate change while strengthening communities. At EastPoint, for example, Gardner and Waugh decided to renovate to ensure local residents knew they were reinvesting in their existing community—building up familiar structures in new ways. “We really wanted to make use of the existing fabric,” Gardner says. “We like going in and being part of a project that catalyzes neighbors.”

According to local residents, it’s working. “Last year, EastPoint hosted the first Christmas tree lighting service in our community since the 1970s,” Nice says. “It was held in the open breezeway. The kids were so excited to see a Santa that looked like them, which many had never seen before.”

Nice pauses. “This transformation has had a great impact,” she says. “It went from an empty, boarded-up building to a place where you can have community engagement. It has awakened and renewed our spirit in this area of our community.”

Inside EastPoint

How the EastPoint Project in Oklahoma City creates sustainability in both the structure and community. Hana Waugh, AIA, formerly of Gardner Architects, describes their vision.

Reuse Existing Building: “Reuse is the strongest green aspect of this project. It produces a much smaller carbon footprint than building something new, and we adhered to regulations for Low-E windows, roofing, insulation, and other materials.”

Engage the Community: “The tenants live in the surrounding neighborhood. Rather than bring in people from a different part of town, the idea is to help sustain and invest in the community that is already there.”

Maximize Natural Space: “An effort was made to connect the north side of the site to the south side through the breezeway and sidewalks that wrap around the perimeter. We added an outdoor patio, lawn, and gathering space for families to enjoy.”

Give Tenants a Stake: “The way that the developers structured rent and ownership opportunities for tenants is hugely impactful. Tenants are able to put down roots and gain 15 percent equity in a place where they’re investing their time and resources, which will add value to the neighborhood and likely keep business invested in the area longer-term. I consider purposeful stewardship and listening to the needs of the tenants some of the most impactful ways to contribute to sustaining the existing community.”

Stopping Climate Change

Finally, renovating existing structures to become net-zero carbon is crucial to achieving the most important goal of our time: addressing climate change. According to the nonprofit Architecture 2030, the world needs to reduce fossil fuel CO2 emissions by 65 percent by 2030, and then to 0 percent by 2040, and renovating structures can play a key part. More than 90 percent of all buildings expected to be standing in 2025 are already built. This means the embodied carbon, which is responsible for 72 percent of all CO2 emissions of new buildings, and 11 percent of general emissions worldwide, has already been spent. Architects have an opportunity to renovate these buildings to reduce their carbon emissions to zero and help meet our carbon goals. “This is a wonderful moment to promote green renovation and jump-start the economy,” Carroon says. “If people continue to work remotely, we may see them moving from cities to the Main Streets of America and revitalizing historic buildings. And it’s our job to help them—that’s the power of design.”

Smart Renovations to Reduce Carbon Emissions

How existing buildings can be modified to become net-zero carbon

- Establish Clear Goals: Beyond energy and resource conservation, retrofitting may also serve economic and social objectives. Architects who frame a renovation with these goals in mind are more effective advocates for sustainability add value to their service.

- Unlock the Existing Building’s Full Potential: Many older buildings have good passive bones, with features like thick masonry walls that mitigate temperature swings and tall double-hung windows that provide access to daylight and allow rooms to self-ventilate. These create opportunities for lower-carbon design.

- Prioritize the Most Effective Interventions: Start with a thorough inventory of what you’ve got, then target your upgrades and evaluate potential design solutions. Consider the building as a whole system—including the potential for on-site renewable energy—and then bring the whole project team together early to advise on potential synergies.

- Consider Total Carbon Impact: Operational and Embodied Energy: In addition to more efficient operations, reducing embodied emissions is essential to stopping climate change. Savings can be achieved by retrofitting existing buildings, minimizing the materials needed to do so, and using low-carbon materials.

- Consider Health Impacts of New and Existing Materials: Conduct a hazardous-materials inspection at the outset of the project. Some materials, such as asbestos in flooring, may be safely encapsulated and left in place. Other materials, such as lead, will need to come out. Then look for ways to select new materials to improve the health of occupants.

- Design to Accommodate Future Change: Much of the value of an existing building lies in its ability to adapt to new uses. Think in terms of loose fit: How can your project achieve its goals so that the building remains adaptable? Can you identify ecology and habitat restoration through site landscaping and green roofs, which also manage stormwater runoff and help with insulation to improve efficiency? Designing for flexibility extends the life of the building and provides future generations with further chances to retrofit.

- Look into Light Renovations: “We’re seeing more clients interested in light-touch renovations, which allow you to tweak or repurpose buildings, spend less money, and still reap benefit,” Carroon says. “It’s challenging and can really test your design chops, but it's also exciting.”

- Repurpose Materials: “Places like Portland and San Antonio are taking the lead on diverting construction waste by saying, ‘If you’re going to take a building down, then you have to disassemble and reuse it,’” Carroon says. “This is changing building codes by allowing dimensional lumber and component pieces of existing structures to be reused. If a building is at the end of its life, it can still be an organ donor.”

- Do Smart Retrofits: “A smart retrofit isn’t gutting the inside of a building to the studs,” Carroon says. “It’s working with what's already there. This is a better strategy for energy and materials, and preserves more of the historical fabric. If we can create an economic system that allows for more durable materials instead of this constant downgrading, we’ll stop seeing materials that have to be replaced every 30 years and instead last for 100 years.”

The Blueprint for Better campaign is a call to action. AIA is asking architects, design professionals, civic leaders, and the public in every community to join our efforts. Help us transform the day-to-day practice of architecture to achieve a zero-carbon, resilient, healthy, just, and equitable built environment.