In 2021, a collection of mayors from the American heartland traveled to Scotland to attend the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26). Their mission? To join global leaders like President Joe Biden and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson in discussing ways to limit climate change and improve communities through resilient design.

“I went to COP26 as one of 100 mayors working to improve resilience and protect towns along the Mississippi River,” says Belinda Constant, the mayor of Gretna, Louisiana (population 17,000). “Coastal erosion, greenhouse emissions, and saltwater intrusion into freshwater rivers are huge concerns, and what affects my colleagues in Minnesota also affects me in Louisiana. So we’re finding collective success by becoming one voice.”

Constant is one of 30 mayors who are banding together to limit the effects of climate change in communities along one of the longest river systems in the world—the Mississippi. Stretching 2,350 miles from the river’s source in Lake Itasca, Minnesota, to the Gulf Coast, the Mississippi River Basin produces 92% of the United States’ grain exports and is home to 25% of all fish species in North America.

Yet in recent years, climate change has increasingly threatened the 124 communities in the Mississippi River ecosystem. In 2021, after a decade of flooding and high water levels, drought-like conditions in northern Minnesota caused the river and its tributaries to drop—a result of climate change producing greater fluctuations in precipitation from one year to the next. “When you end up with less rain in the headwaters, you get less flow farther south,” said Jeff Boyne, a forecaster with the National Weather Service, in a recent interview. “We’re finding climate change is [causing] rapid changes between periods of very wet and very dry and back to very wet again.”

For communities situated along the Mississippi’s banks, these shifts have disrupted countless lives and resulted in more than $210 billion in damage since 2005. To deal with changing flows both at the river’s headwaters and where it enters the Gulf Coast, mayors from 10 states formed the Mississippi River Cities and Towns Initiative (MRCTI) in 2012 to design natural infrastructure that could serve as a buffer against the rising river, sequester more than 160,000 tons of carbon, and protect communities. “When sea levels rise in the Gulf Coast, it travels up through the Mississippi, and communities everywhere face high water and overflow,” says Errick D. Simmons, the mayor of Greenville, Mississippi, and co-chair of the MRCTI. “Partnering with institutions like Ducks Unlimited and the UN Environment Programme, we’re working to mitigate disasters, improve water quality, and attract ecologically beneficial economic development projects.”

Here’s how MRCTI is collaborating with architects to improve the resiliency of their communities.

Partnering with architects to build consensus

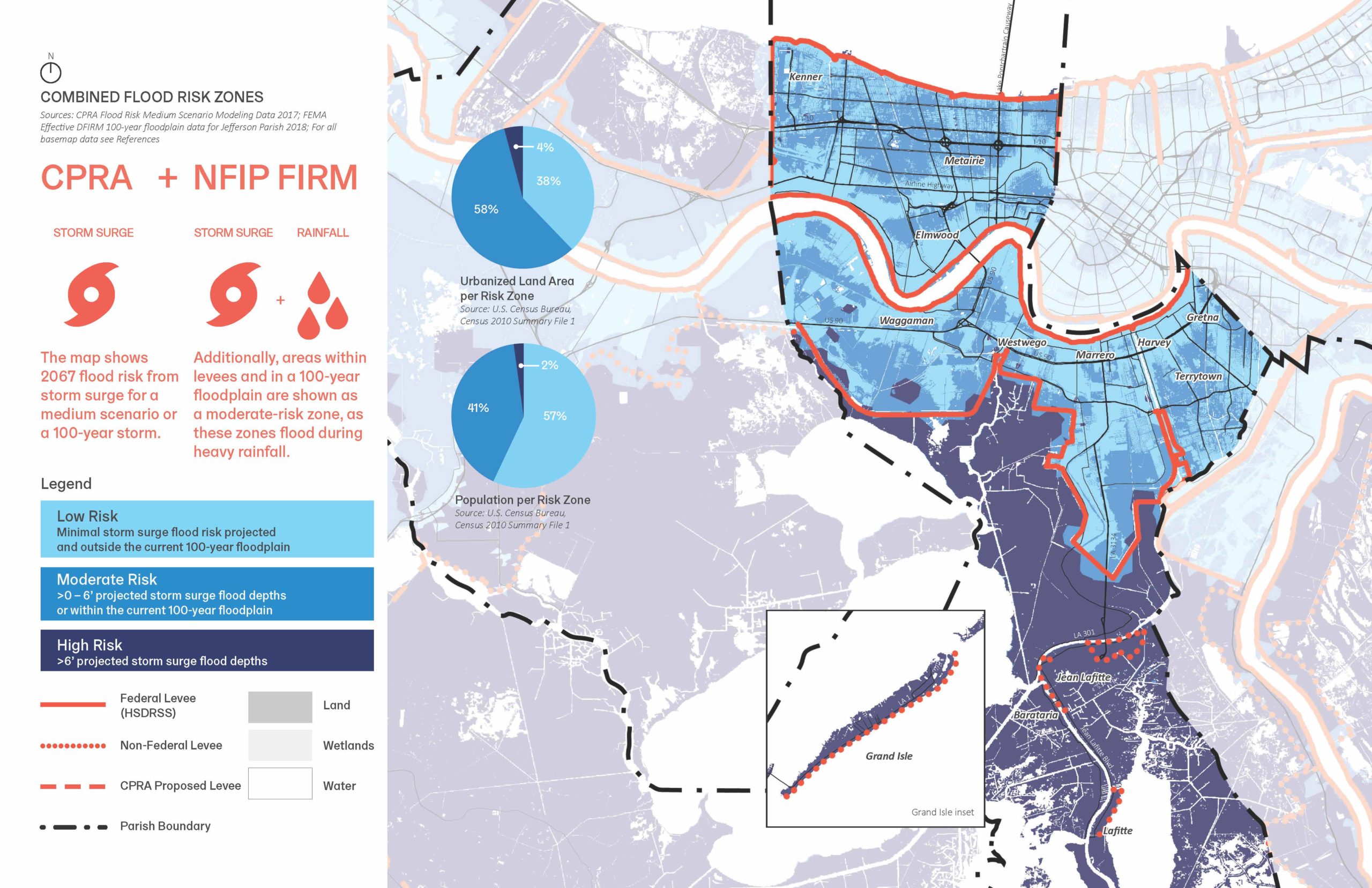

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Belinda Constant, then a councilwoman, knew that Gretna—a town along the west bank of the Mississippi River in greater New Orleans—needed to reimagine its infrastructure. But it wasn’t until she was elected mayor in 2013 that she was able to really do something about it, bringing together architects, engineers, and landscape specialists to reimagine how the community could mitigate flooding from the rising Mississippi. “When I was growing up here, we had summer showers but never flooding,” Constant says. “Now we have these monster hurricanes that used to occur once every hundred years happening annually. So we’ve gotten past the rhetoric and politics as a community and aligned to make change. When you can’t flush your toilet because the streets are flooding, you’ve got to think about resilience.”

One of the mayor’s first projects, identified through the Department of House and Urban Development–funded program LA SAFE (Louisiana’s Strategic Adaptations to Future Environments), was to redesign Gretna City Park, located in a low-lying neighborhood that experienced routine flooding from rainfall. Constant and her team called on Andy Sternad, AIA, an architect with Waggonner & Ball in New Orleans and one of LA SAFE’s lead planners, to help reimagine the park, both in terms of everyday use and with a view to flood mitigation. Located on the back slope of the Mississippi, the park was quickly inundated during storms, and surrounding homes suffered one of the highest repetitive-damage rates in the country. To build consensus for redesigning the park, with added retention areas as well as new features—including a pavilion, a meadow, and ponds for kayaking—intended to increase use, Constant and Sternad held a series of public meetings. Their goal was to identify how a resilient new park design could save homes and money and improve quality of life even when it isn’t raining.

Gretna Resilience District, Gretna, Louisiana

- Gretna City Park is located in a low-lying, high flood risk neighborhood on the back slope of the Mississippi River in Jefferson Parish, one of six parishes in the LA SAFE adaptation strategy. The flooding is so significant that surrounding homes suffer some of the highest repetitive-damage rates in the country. (Image: Waggonner & Ball Architecture/Environment)

- The redesigned park is the first pilot project to break ground for the LA SAFE Program and is funded through HUD’s CDBG-NDR program. Waggonner & Ball served as lead designer and planner for the overall LA SAFE program. (Image: Waggonner & Ball Architecture/Environment)

- This 80-acre project is a demonstration of nature-based flood mitigation plus new habitat and recreational opportunities added to an underutilized public park. Most importantly, the resilient design saves homes, money, and improves quality of life even when it isn’t raining. (Image: Waggonner & Ball Architecture/Environment)

- To build consensus for redesigning the park, Gretna’s mayor mobilized her constituents to vote for funding after three rounds of public engagement during the LA SAFE program. The Waggonner & Ball team built on these relationships with additional public engagements throughout the design process. (Image: Waggonner & Ball Architecture/Environment)

“We educated the community about how we live with water,” Constant says. “As a mayor, you never have enough money to do everything you want to do, but you’ve got to get in the game of resiliency. Then educate your community, get them entrusted in the vision, and work with engineers and architects to explore opportunities for resilient design and community building along the way.”

Bringing everyone on board to lift everyone up

Three hundred miles northwest of Gretna, Mayor Errick D. Simmons of Greenville, Mississippi, is dealing with the same climate-related challenges, with the rising river threatening communities located along its banks. Nearly a century ago, the Great Flood of 1927 broke levees north of the Delta town, the raging water covering a million acres to a depth of 10 feet in 10 days, with Black communities being forced to risk life and limb and repair the levees without pay. “Black folks were left along the banks to be used as sandbags and die,” Simmons says. “We all remember that. But even today, the flooding that happens in Greenville mostly impacts the people in Ward 6, which has a 99% Black population. So we have to address that.”

A former councilman in Ward 6, Simmons understands the importance of engaging local communities to help move past tragic history, and now uses his leadership position in MRCTI to help draw federal and international support to the Mississippi region—funding local projects and improving social equity in the process. In Greenville, the entire community is impacted when the river floods. But it disproportionately affects residents in Ward 6, causing toilets to overflow and even destroying a wastewater treatment plant. So in 2021, Simmons announced a $7.7 million economic development administration project from the South Delta Planning and Development District to make those neighborhoods more flood resilient, with the city council matching that grant with an additional $8 million.

Uniting with state representatives, corporations, and federal institutions like the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Simmons got the plant up and running again and built up acres of absorbent shoreline to serve as a buffer when the river rises.

“That’s a $16 million project,” Simmons says of the Ward 6 plan. “Because not only do we want to make sure we address climate infrastructure, but we also want to make sure we address our historically neglected Black communities.”

“The key strength architects bring to the challenges we face is the ability to see multiple viewpoints, wrap them together, create a narrative that leads to new solutions, and then build coalitions of people working together in new and different ways to solve problems we haven’t faced before on this scale. We have a unique role we can play in helping mayors and civic leaders create a plan to move forward.” —Andy Sternad, AIA

Architects helping to better build back the Mississippi

Going forward, Simmons says, the MRCTI welcomes and encourages collaboration with architects to help towns and cities along the river incorporate resilient design that enhances infrastructure and strengthens community, something Sternad has seen accomplished in Gretna with resources like the AIA Framework for Design Excellence.

“The key strength architects bring to the challenges we face is the ability to see multiple viewpoints, wrap them together, create a narrative that leads to new solutions, and then build coalitions of people working together in new and different ways to solve problems we haven’t faced before on this scale,” Sternad says. “We have a unique role we can play in helping mayors and civic leaders create a plan to move forward.”

There are numerous ways architects can get involved with communities. The government of Wisconsin, for example, is using the AIA Framework for Design Excellence to create resilient design throughout the state, pioneering new ways to draw on architects’ skills to enhance communities beyond project boundaries. AIA has an ongoing partnership with the U.S. Conference of Mayors as well as the Mayors Innovation Project, and the AIA Resilience and Adaptation Certificate Series and Regional Tour of Climate Risk for Planning and Design are great resources for climate adaptation and resilience. “AIA has invested significantly in resources for mayors,” says Julie Hiromoto, AIA, a principal architect at HKS in Dallas. “At a local level, civic leaders have so much autonomy, potential, and opportunity—and architects can be great partners for identifying value-add opportunities, investing in our built environment’s infrastructure, and rebuilding with the community’s needs in mind.”

For mayors like Simmons, the work along the Mississippi River reflects a broader aim to create a better world, with local changes delivering greater impact. “We have to begin addressing the global issue of climate change at the local level,” he says. “How we all come together in our local communities can help people everywhere.”